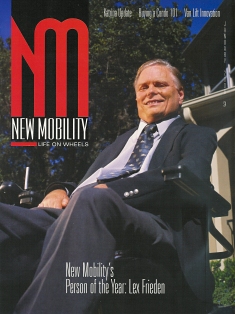

Lex Frieden: Prepared for

Disaster

By Roxanne Furlong

|

During those harrowing first days after Hurricane Katrina blasted through Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama, ILRU received a call from the Federal Emergency Management Administration asking for referral help for storm evacuees who have disabilities. Within hours Frieden gathered his staff of 20, and they began working shifts to field what quickly became 300 to 500 daily calls from their traumatized neighbors to the east. Many people were in hopeless situations -- some even suicidal. Not long after, ILRU staff were answering calls from Hurricane Rita evacuees. Frieden spent days and nights on the phone trying to find resources to help as many evacuees as possible.

"He felt deeply moved," says Laurie Redd, administrative director of ILRU. "He was constantly watching to see what was happening, talking on the phone trying to get resources to people and find out what was going on.

"Everything was so disorganized, not only with FEMA but with other disability organizations. They were wiped out in New Orleans. He was making a lot of calls trying to get help to people. I was very worried about him. He wasn't sleeping."

|

But when Frieden took action on behalf of the victims of Hurricane Katrina and Rita, it wasn't just from his own ordeal of being imprisoned for six hours in waist-deep, muddy sewage water. Long before his own brush with disaster, Frieden had exhibited a strong desire to serve others. The unselfish heart of this soft-spoken, straightforward Southern man had been developing for decades. He knew long ago that civil rights are for all people.

Problem

Solver

Lex Frieden was born in 1949 in the rural town of

Alva, Okla. The town was the county seat, had about 7,000 residents and was home

to a small teacher's college, Northwestern Oklahoma State University. His was a

homogeneous upbringing: Everybody in town knew everybody else, there were good

schools, close-knit families, and it was a long way from the radical social

change of the anti-establishment movement occurring in California, not to

mention the race riots in Alabama.

Frieden had a younger sister, his father worked as a professional in town and his mother stayed home and took care of the house and her two children.

"Despite the fact that it was a small town, there was plenty to do," he says. "We had a movie theater, a Dairy Queen, there were always sporting events at school and I enjoyed playing the trumpet in band and working on school projects."

|

"Growing up in a little town in Western Oklahoma, there are certain kinds of interpersonal loyalties you have to these people. You've got to live with the people that you grow up with or you're going to be a very lonely person. So you learn how to get along with other people. It gave me a lot of inner strength and support," he says. "We were here in our center of the world where everything seemed to be in its place."

It was also about the time that NASA was expanding and mankind was reaching for the moon. That interest in science inspired a lot of people, including Frieden, who did well in school. He was the class valedictorian of Alva High and voted "most likely to succeed" by his classmates. As a result of his hard work, he received several academic scholarships and in 1967 began taking classes in the electrical engineering department at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater.

During his first semester as a freshman, Frieden broke his neck in a car accident, sustaining a spinal cord injury at the C4-5 level. After recuperating in a hospital in Oklahoma City, Frieden went to The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research in Houston. It was here at TIRR that Frieden met a gifted doctor, Dr. William Spencer, who was in the process of changing the practice of rehabilitation. Spencer became Frieden's mentor.

"When I was in the rehab center, they told me 'Look, you can do about anything you could've done before your injury if you can figure out how to do it from a wheelchair,'" he says. "At the time, that did not seem terribly like it was a great task. Goodness, we were sending men to the moon! Here I was on Earth and my only limitation was being in a wheelchair."

When his father was transferred for work to Tulsa, Frieden applied to the University of Tulsa. He and his father met with the dean of the college and dean of students. There were no building entrances without steps, so they met in the school parking lot. The deans invited Frieden to come to their school, pointing to a building that was being built in the modern architectural style of the late 1960s: ranch-style, no steps. They handed him a catalog and told him the new building would house any class Frieden might choose to take during his three years on campus. He signed up.

"They were smart," Frieden says. "They had that Oklahoma problem-solving ingenuity. It was a sensible thing to do. If you can't get the person inside the building with all the steps, put them in the building without the steps and move the classes to them. It doesn't take a genius to figure that out. You just have to break down the barriers in your thinking to come up with a solution." Which is exactly what Frieden has done for the past 35 years.

Changing the

Paradigm

While at TU, Frieden joined the Alpha Phi Omega

service fraternity. On Saturdays, he and his fraternity brothers would go out to

the community and perform service projects. He graduated in three years with a

major in psychology, received a scholarship from the University of Houston for

academics and teaching and became a teaching fellow in psychology -- he later

received a master's of arts in social psychology.

|

TIRR's IL program was the brainchild of Spencer. It was one of the first such programs in the country, started around when Ed Roberts and Fred Fay were starting their programs in Berkeley and Boston, respectively. Spencer's forward thinking resulted in a communal living program that allowed wheelchair users to live independently and go to school and work.

"From him I learned about the importance of having a variety of skill sets and educational backgrounds and training to help solve complex problems," Frieden recalls. "Before Spencer began to influence the field of rehab, people with disabilities were treated just like most people in a hospital: They had a single doctor who was responsible for them.

"Spencer figured out there was no single doctor who had the knowledge necessary to help someone with a complex series of issues like those of us with severe disabilities. He understood that a person who had polio or SCI or a muscular disease not only had the root cause of their injuries but may need more than a neurologist."

Frieden says Spencer's teaching and practicing of multi-disciplinary approaches to solving complex problems occurred before it was standard practice. He also treated physical therapists as part of his team and included the patients in team meetings.

In 1974, six years post-injury, Spencer sent Frieden to Washington, D.C., to meet with members of Congress about funding independent living centers. While Frieden developed training, assistance and service programs that would facilitate decision-making on the part of an individual with a disability, Spencer was doing the same with the medical community.

Frieden -- then only 25-years-old -- explained to several members of Congress how this philosophy could be applied to programs run by people with disabilities. He believes that this, coupled with what Roberts and Fay were doing, is what laid the groundwork for the amendment to the Rehabilitation Act in 1978, which included provisions for funding 10 grants for independent living centers.

"There are others who are famous," says Yoshiko Dart, wife of the late beloved disability leader, Justin Dart, "but we consider Lex to be one of the founders of the independent living movement." The Darts are widely revered as pioneers in the disability advocacy movement of the '70s and '80s. "But it was Lex who started this new option, different from the California model," Dart says. "Lex doesn't seek the limelight, he just wants to get the job done."

Policy

Maker

Frieden spent the late 1970s developing independent

living centers, lobbying to get independent living included into law, providing

technical assistance to states and -- with the Darts -- visiting every state

promoting the idea of independent living centers. For Frieden, the initial ideas

of the centers flowed from Spencer's philosophy, but Frieden added the wrinkle

of consumer control.

|

"He worked for four years," Yoshiko Dart says. "He has an enormous capability to store a lot of knowledge and experiences. He is an extremely intelligent and fiscally responsible person. I've never seen him get angry or shout even in real tough situations. Yet he's positively frank and straight to the point."

NCH held public hearings around the country, commissioned a number of reports and researched policy needs and the practical needs of people with disabilities. On Jan. 29, 1986, Frieden and several others had an appointment with President Reagan -- complete with a much-anticipated press conference -- to present Toward Independence. The report was expected to make national news and get the press it deserved. Everyone would be talking about it.

Tragically, the day before the presentation, the space shuttle Challenger exploded, and the president's schedule was cancelled. It was suggested that the presenters meet with then Vice President George H.W. Bush. The vice president's staff told them they would have 10 minutes and a photo op.

"We went into the West Wing office of the vice president and he started talking about the report. He had read the report!" Frieden says. "He spent an hour and 15 minutes asking questions and talking about his family and how he understood disability issues. He wanted to be an advocate."

Two years later NCH produced a report called On the Threshold of Independence, which included a 13-page draft of what eventually became the ADA.

In 1988, after the ADA was first introduced into Congress as a bill, Frieden left his federal-employee status at NCH and moved back to Texas to lobby Congress to pass the bill. Those in the disability advocacy movement spent two years educating America about the need for the legislation. By the time it came before Congress for final passage, it had overwhelming support and was passed by the largest margin of any civil rights bill, ever.

Four years after Toward Independence, President George H.W. Bush -- who considers this his proudest moment in domestic policy -- signed the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Flash Forward to a Flash

Flood

On June 8, 2001, Tropical Storm Allison blew into

Houston. For 10 hours Allison dumped about 4 inches of rain per hour. The people

of Houston thought they were safe until the storm worsened and became even more

dangerous than weather services had predicted. Torrential rains came down all

day and into the evening. The earth was dry and there was too much rain to

absorb. The water began to seep into Frieden's home. Sitting in his power

wheelchair in his living room, Frieden watched helplessly as floodwater rose

throughout his home until it reached to his waist, all within a 30-minute time

span.

|

"I knew intellectually that either this was going to be a Biblical flood where everybody dies, or the water was going to level out because the higher it goes, the farther it spreads out," Frieden says. His wife, Joyce, and grandson, Trey O'Connor, were both out of town during the storm. "Houston is a fairly flat city so I knew at some point the water was going to find its level. But it stayed waist-deep for about six hours. I felt like I was stuck in a swimming pool."

Then, he says a weird calm came over him and he began to enjoy and marvel at what was happening around him. His 6-month-old puppy -- too short to walk around and unable to get footing to jump onto Frieden's lap -- dog-paddled throughout the house. The puppy soon found a bone floating in the water and happily paddled around with it in its mouth. At one point, a paint can came floating by, and Frieden had no idea where it came from. He eventually had to tell his two assistants to sit on the couch with the puppy: every move they made sent waves of water throughout the house, knocking collectibles and papers off desks and shelves. But paper, dog bones and paint cans weren't all that was floating around.

The Frieden home is situated next to a drainage river that flooded for the first time in 50 years. Upstream from their home is the city sewage plant, which also flooded, sending oozing raw sewage everywhere, including into Frieden's living room. Whatever was on the ground was floating in the water. He worried about the slimy, slick oil and chemical fertilizers floating on the surface, and he worried about bugs and parasites in the dirty water. There was no way to call for help. All land lines and cell phones were inoperable.

When the water finally receded, Frieden says it was as if someone pulled a bathtub plug: Within what seemed to him like 10 minutes the water drained from his home. When he was able, Frieden started making calls for help. A vocational rehabilitation counselor, who showed up before the Red Cross did, sent an expedited assistance request to order replacement medical equipment. Even so, it took six months before Frieden received his new chair, so in the meantime he borrowed a power chair from his local independent living center.

Year of the

Hurricane

After Katrina hit -- and because his experience

with Allison had prepared him -- Frieden had the ILRU clearinghouse up and

running before Red Cross got out to anybody. Frieden knew from experience that

people would be waiting a long time for help from larger organizations. What's

more, he says most Red Cross volunteers don't understand that people with

disabilities have immediate needs. Frieden and ILRU answered questions from

evacuees and guided them in the right direction.

Frieden's experience with Allison was not the only event that prepared him for the hurricane disasters of 2005. "Because of his multiple hats, he'd given some recommendations post-9/11 to the secretary of Homeland Security," says Mark Johnson, director of advocacy for Shepherd Center in Atlanta. "During the hurricanes, there was a lack of response from FEMA and mainstream organizations like Red Cross. This was like deja vu for him -- he could relate a lot to the folks who had not been evacuated and now were dealing with transition. The ILRU became ground zero for a lot of independent living centers to get advice about how to support people in the gulf region or around the country."

Frieden explains that because the Red Cross advertises and gets a lot of donations, people have high expectations of the organization. "But their ability to deliver services is severely limited by their structure," he says. "When I needed it, I got a lot more help from my independent living center and vocational rehabilitation agency than I did from the Red Cross."

Overwhelmed by incoming calls due to Katrina, ILRU developed a triage to sort resource requests from evacuees. All 20 employees took turns either answering and routing calls or returning messages. Unable to help with financial needs, they mostly referred callers to available resources and coached them on asking for help.

"We were told people would set their alarms during the night so they could call FEMA because their lines were so busy during the day," Redd says. "FEMA would give them our number and they'd call us and leave a message. We had daily staff meetings for problem solving. We'd present an issue, or relate calls we'd received and share ideas and new resources," she adds. "We filled out forms on each caller and compiled a lot of important data on what happened to these people during the emergency."

To make sure every evacuee housed in Houston's two temporary shelters received needed medical attention, ILRU -- along with other entities -- set up a medical evaluation processing system for admission.

"Our city did a remarkable job and in the process, we learned how to do it better the next time," Frieden says. "I took a film crew to the George R. Brown Convention Center and interviewed the people responsible for setting up these centers and admissions programs. We're going to produce a training film."

Based on the clearinghouse experience, ILRU's staff has put together a handbook on technical assistance for disabled victims of hurricanes that it will soon publish.

"We were called to service," Frieden says. "These were our neighbors, and they suffered very much the same kind of trauma as we did when Tropical Storm Allison came to Houston in 2001. We knew Katrina could have hit Houston just as easily as it hit New Orleans. We knew people needed someone to talk to, to provide guidance and organize their thoughts. We were committed to helping these people."

Toward InclusionFrieden says that when the ADA was written, the early advocates of the disability movement saw an "opportunity on the lip of the cup" that they didn't want to miss. Expectations were high, many of which have been met.

"You don't have to go very far from your home to see the impact of the ADA," he says. "Just as far as the parking lot where you see accessible spaces or out to the street where you see accessible busses. Fifteen years ago, half the buildings didn't have ramp access and there were no captions on televisions.

"But we need to accommodate people with disabilities who wish to live and who do live in rural areas -- just as we try to do so in urban areas," he urges. "The reality is every public transit vehicle in every big city in America by now is probably accessible. Only 15 years ago, you couldn't say that about any city in America."

|

"But the public authorities provided no transportation for those people without transportation -- disabled or not," he says. "In the case of Rita, the paratransit system in Houston for three days prior to that storm was hauling people out of their homes and up north. Houston had a plan and they followed that plan. I don't think New Orleans had a very good plan, or if they did, they didn't follow it.

"But, because of the damage Katrina did," he adds, "a lot of people got scared during Rita who did not live in threatened areas, and they started leaving too, which created a huge traffic jam."

Frieden knows that life is all about coping with challenges, and he tries his best to foster solidarity and inclusiveness. "Some of us are challenged to cope with physical challenges, some with mental challenges, others with sensory impairments," he says.

When Frieden was living at TIRR in the early 1970s, there was a halfway house down the street for people with mental retardation. One man, Mac Brodie -- mistakenly placed in the halfway house -- visited the TIRR dorms looking for volunteer work.

Brodie was injured as a medical corpsman in Vietnam at the age of 18. He sustained brain damage, causing severe memory loss. Each day his mind is like a blank slate. At TIRR, he did his best to help residents, but many lost patience and wouldn't work with him. Frieden patiently guided Brodie and taught him to be his assistant.

"That was an awakening for me before I actually got started in the advocacy movement," Frieden says. "It's about the extent that you can build an environment that promotes good quality of life. From Mac's standpoint, by helping me, he's found a helper."

Frieden is now 57 years old, can still recite the Boy Scout oath and will continue to work with his local and federal government to provide better evacuation for individuals with disabilities. He and Joyce, who also uses a wheelchair, will celebrate 30 years of marriage this year. Their grandson will soon be graduating from high school, and after 35 years of friendship, Frieden and Brodie are still working together, having formed a brotherly bond.

After the 2001 storm, the Friedens rebuilt

a fully accessible house, poised 3 feet above ground level. Now when it rains,

the water runs down the street. It's a simple solution when you think about it.

But not everyone lives in circumstances that allow for simple solutions.

Sometimes it takes a whole community supporting one another to make it through

disasters such as Katrina. And thanks to Lex Frieden, we'll be better prepared

the next time around.